Hot off the Press!

www.pedropanbook.com

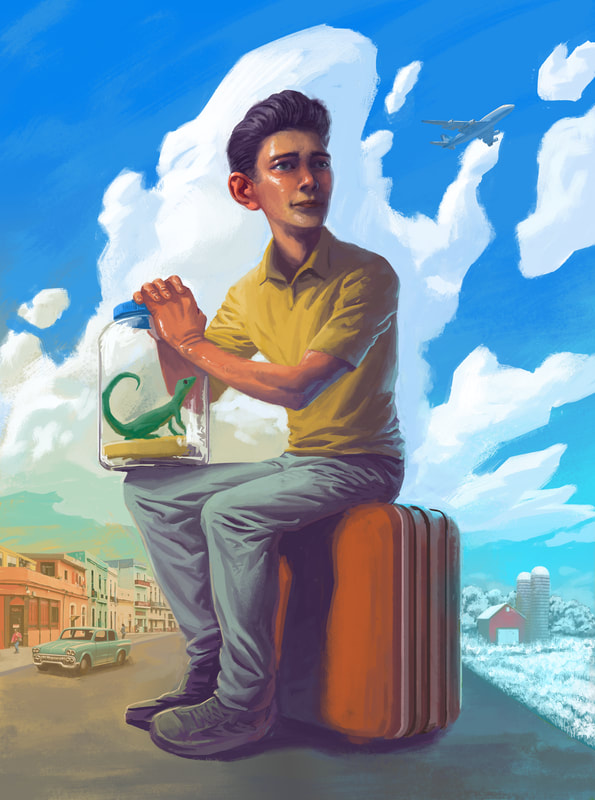

Pedro Pan: One Boy's Journey to America.

Story by: Michelle Marie McNiff

Cover art: Kurt Huggins

Pedro was a young boy who lived near the seashore on a tropical island where the palm trees swayed in warm ocean breezes. The boy lived in Havana with his mother, father, and grandmother, Abuela as he called her. Their oceanfront home was a modest two-story blue house, the same robin-egg color as his father's two-door blue sedan. Many of the houses were painted in splashes of vibrant colors. Pedro called the pink house next door the flamingo house, and the home down the street the yellow canary. The bright blue house on Calle 11 had swirly iron gates and terrazzo-tiled floors that turned cold in the short winter days. The weather in Cuba was warm and humid most of the year.

Pedro and his parents slept upstairs, and his grandmother slept alone downstairs. She had lived in the home her entire life and was now so old and frail she no longer had the strength in her knees to walk up and down the stairs. While Pedro’s grandmother had given birth to her children inside the home, Pedro was born at the hospital where his father worked. His grandmother sat on the front porch and knitted a quilt blanket. The neighborhood cats lounged beside her as she swung back and forth in her wooden rocking chair. The feral cats sunbathed on the porch, stretching, licking their paws, hoping to catch a songbird. Their eyes flickered from the porch to the balls of yarn tumbling inside her basket as she knitted. If a cat pounced at her yarn strings, Pedro’s grandmother would stop her stitching and reprimand the feline offender, "No, no gato, no, no cat, no pounce."

To add emphasis to her order, she waved her arms abound, up and down, left to right, as if she were knitting in the air. "No, no gato, no, no cat, no pounce," she repeated. Pedro sat cross-legged next to her on the floor reading his picture books. He flipped through stories about pirates and lost treasures, dreaming of that faraway paradise called Neverland and, a pale princess who lived with seven colorful dwarfs. His favorite story chronicled the adventures of a girl named Dorothy, who lived on a Kansas prairie. One day, a cyclone lifted her farmhouse off the ground and transported it to the magical land of Oz.

"Abuelita, can a hurricane blow our house into the sky?" Pedro asked, looking up from his book.

"Oh no," she replied. "Our home can withstand any storm. We shutter the windows and doors, and we ask our Lady of Charity for protection. Those books you read are made to entertain your imagination. Do not worry like an adult, think like a child for as long as you can, and never, ever lose hope, no matter what may come."

A sculpture of Our Lady of Charity, the Patroness of Cuba, rested next to a glowing white candle in the living room. Her loving eyes seemed to follow Pedro around the house. The crown on her head sprouted rays of gold just like the sun. She held her infant son in her arms, and wore a long, flowing blue cloak and a white gown. At her feet, three young fishermen sat inside a small boat. They looked up at her in gratitude for calming the sea during a violent storm.

When Pedro stood in front of the statue, he saw himself in the rickety fishing boat. He had brown skin, just like two of the fishermen inside the boat. The shrine to the Cuban Mother comforted Pedro. If he were ever in need, he could call on her. Every Spanish country had a mother statue of its own.

The second floor of the house had a spectacular view of the north Havana shoreline. A long, curved balcony floated across the entire top floor like the starboard bow of a cruise liner. Like most children his age, Pedro had a vivid imagination. Facing out to sea, he would imagine himself as the captain of the balcony ship.

"Ahoy, mates!" he would shout, "I see land ahead, ahoy mates!"

Pedro listened to his voice bounce off the tiled wall and marble floors, "Ahoy, mates! I see land ahead, ahoy mates!”

Wearing a sailor’s cap and holding a telescope made from construction paper. Pedro would observe the changing emotions of the sea. On this sunny day, the ocean looked content, the waves were calm, and the coastal water sparkled as bright as diamonds. On rainy days, the sea turned angry, with choppy waves under a blurry haze of dark clouds. The sea would thunder and roil in anger as it crashed over the Malecón waterfront. Pedro longed to see a mermaid splash over the thick concrete walls. If that happened, he would rescue her from the sharks and pirates. Pedro had seen many fish flop out of the water, but he had never

seen a beautiful mermaid fall onto the seaside boulevard.

Suddenly, a cold wind blew in from the west. A furious wave splashed onto the pedestrians walking alongside the Malecón. It was a Saturday afternoon, the day when the teenage boys hung out on the sidewalk next to the old fishermen at the sea wall.

Pedro chuckled as he watched a stream of saltwater cascade over their heads, soaking their clothes and shoes. His belly ached as he laughed, watching the boys scatter like drenched rats. Then he counted how many times the sea would splash again, "1, 2, 3, 4, 5, splash, splash, on top of your heads."

The old fishermen did not flinch, and just steadied their fishing lines. The teenage boys used their fingers as combs to fix their hair as the pretty girls strolled by the seawall. A musician followed behind, playing his violin in hopes of earning his next meal.

When Pedro was not home, he spent most of his days at school. His teachers were nuns dressed in black and white habits. He sat in the front row next to Gladys, a classmate he had known since kindergarten. She had long brown hair pulled back in a thick braid. A red ribbon tied in a bow held her hair together on the top. When she smiled, a dent formed in her cheeks.

"Those are dimples," his father explained, "The indentation on her cheeks is a weakened facial muscle."

Pedro did not like that medical description; Gladys was perfect in his eyes, and she made him smile from ear to ear.

Everyone in the Vedado barrio knew his father. The neighbors knocked on the door for medical advice when they were not feeling right. On Christmas morning, the front porch was full of fruit and food baskets left by those he treated. Leaving the gifts was how the community thanked Dr. Infante for taking care of them. He did not charge the neighbors who knocked on the

door. And Dr. Infante made house calls, wearing his stethoscope around his neck, and carrying a bulky leather bag with loop handles as he walked to a neighbor's home.

"We Cubans, must take care of one another," his father said, "Our family tradition of caring for the sick and wounded has passed on through the years. My grandfather, his father, and his father were doctors. One day you will take my place, son."

Pedro nodded his head in acceptance of what his father had said, but he could not think so far ahead of his young life. He was just a boy who enjoyed baseball and dreamed he would play for the New York Yankees one day. Pedro loved his oceanfront home in Havana and his loving family. His mother and grandmother took good care of him. In return, he was well-behaved−he did his schoolwork, brushed his teeth, and said his prayers before going to bed.

His mother had taken over most of the chores around the house, and his father worked outside the home. At the same time every morning, Dr. Infante left for work, checking his gold pocket watch that was attached to a chain on his vest. And every day, he arrived home at the same time, rechecking his pocket watch, as he opened the iron front gate. His father had a

watchful eye that constantly checked the time and weather. When the winds changed direction, he could predict when a storm was coming. On many weekends, he took Pedro fishing just before a storm, which was the perfect time to cast their lines as the fish were very active near the sea wall.

When Pedro’s dad arrived home at eight in the evening after a long day at the Havana Hospital, the Morro lighthouse would toll, a signal that Pedro should come home after playing outside. It was time for the family to eat dinner, a meal cooked most of the day in a large pot with garlic, onions, rice, and beans mixed with fresh fish or butchered meat from the market. The fragrant spices of the dish filled the house. The Infante family ate dinner together every night at the table. As they held their silverware, their hand gestures expressed the events of the day.

A special dessert, made from one of Pedro’s grandmother’s recipes, was served after dinner. On many occasions, Pedro helped his grandmother in the kitchen, stirring in the vanilla extract, sugar, eggs, and milk. When his father was not in the room, she would let him lick the wooden spoon clean.His grandmother compared the custard flan ingredients to the mix of his skin color.

"You see, Pedro," she said lovingly, "You are like this flan; you have a blend of white milk and caramelized sugar. And you, my grandson, are as sweet as azucar, sugar."

Pedro watched her pour the dark caramel into a baking dish as he identified with the melted mix, for he, too, had a blended color. His grandmother always knew how to make him feel special.

"Go outside and play with your friends," she said, "I will clean the dishes. If the boys pick on you for the color of your skin, you tell them you are a perfect flan, made with milk, sugar, and love."

That evening before dusk, Pedro sat on the front porch and watched the neighborhood boys run through the sea grape bushes. They chased skinny lizards with straight tails and plump lizards with curly tails. Pedro followed their sinister game down the block.

He watched the boys take small pebbles from their pockets and shoot them. A green lizard with a curled tail escaped their slingshots and hid behind Pedro. Rodolfo, one of the boys, pulled back the rubber band on his slingshot and hit Pedro in the arm. Pedro blocked his shots, protecting the green lizard with a curly tail. Again, Rodolfo aimed his slingshot and hit Pedro on the shoulder.

Pedro bent down, picked up the lizard, and placed it in his shirt front pocket. The lizard stuck his little head out of the opening as Pedro ran home as fast as he could. The boys chased after Pedro, but his long legs moved like a locomotive engine. At the street corner, Pedro tripped and fell on the uneven sidewalk. He quickly got up, and sprinted as if her were running bases on

the baseball field−all the way home. When he reached his house, he opened the iron front gate and darted safely inside.

Rodolfo stood outside his front door, "We will get you next time, cinnamon boy!"

The boys in the neighborhood called him many names, cinnamon, caramel, or just brown boy.

Drenched in sweat and covered with dirt, Pedro looked down at his jeans, which were ripped at the knees from falling on the street. His grandmother stopped sweeping the kitchen floor and asked him what had happened.

"Pedro, why are you out of breath?"

"Abuela, the neighborhood boys were chasing lizards again,” he said. "But this time, they brought their slingshots. Look, I saved this little green one with a curly, long tail. Can I please, please keep him?"

The lizard tilted his little head and blinked his beady eyes at his grandmother. Pedro studied the little green lizard in the palm of this hand. The lizard tilted his head and blinked his beady little eyes as if thanking Pedro for his brave rescue.

Just then, an idea popped into his grandmother's head. She pulled out a glass jar from the pantry and poked holes on top of the lid with a sharp knife. She pulled some leaves from a plant on the kitchen windowsill and tossed them into the jar.

"Look, he can breathe through these holes. This container will be his temporary home. We will return him to his family when it is safe."

Pedro carefully placed the lizard inside the jar and watched the lizard examine his new surroundings.

"You will be safe with me, mi pequeño lagarto verde, my little green lizard. I will call you,

Pepe."

Pedro felt safe inside his home. He couldn't understand why the boys hurt the lizards; he

couldn't understand why they teased him for his brown skin color.

"Those boys have a drop of Africa in them," his grandmother said as she hugged him tightly.

"Their parents must not have taught them." She then recited a quote by Jose Marti, a famous Cuban poet: “ Love always wins, hate loses.”

"Now go clean up and wash your hands for dinner.”

Pedro picked up the glass jar from the kitchen counter and took his pet lizard, Pepe, upstairs to his bedroom. He placed the glass container on the windowsill, near his lamp, and opened the window. A small fruit fly flew toward the light and into the jar. The green lizard rolled out his long tongue and caught the fly inside his mouth.

His grandmother finished setting the dining room table with China dishes, crystal glasses, and silk placemats. When Pedro climbed down the stairs, he found his parents in the living room, leaning toward the large radio built inside a wooden cabinet. Pedro could not understand what the voice inside the radio said. The man was talking very fast with a loud voice. His father turned

pale, and his mother’s lips trembled.

Pedro tried to understand what was happening; it could not be one of those tropical storms, he thought, it was the end of hurricane season. He bent down close to the radio speaker and listened to a report of a revolution coming to Havana, but some words sounded like another language. Nothing terrible could happen to his homeland, he thought. Our Lady of

Charity protected the Cuban people, this much he knew. Cuba was the paradise land of his

ancestors’ dreams. Pedro could trace his mother's heritage from a small village in Africa and a township in Spain. His father's ancestors were natives from the Taíno Native American tribe. Diversity and unity held the Cuban people together like bookends on a bookshelf.

The winds of change would soon gust over the stalks of sugar cane and coffee berries that rustled in the cool mountain air from the west.

... Copyright 2021